To Restore a Wealth That is Wild: Sandra Dal Poggetto’s Immersive Art

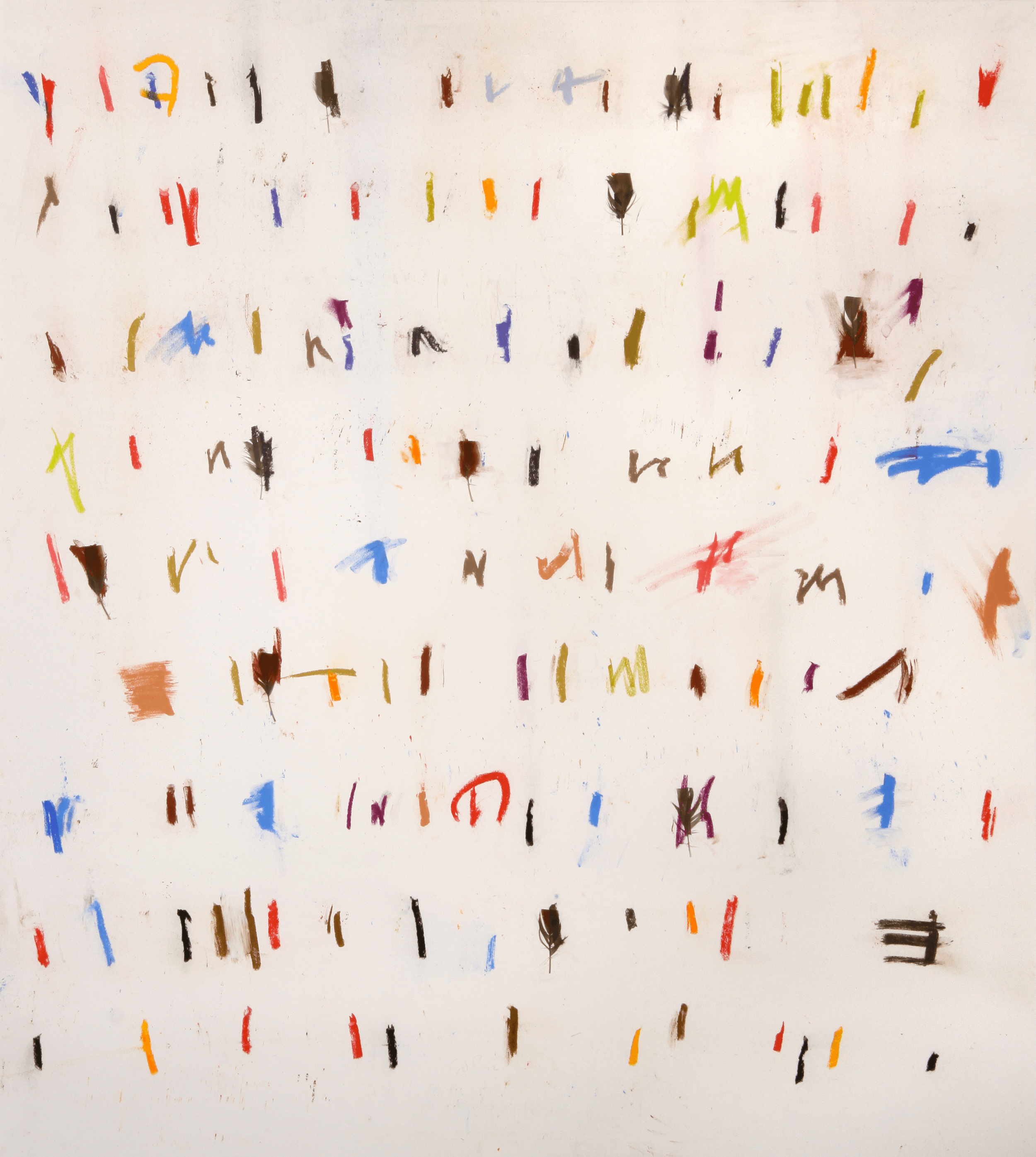

Sandra Dal Poggetto, American Fork No. 16

2017-20, soft pastel, charcoal, chalk, oil, buckskin danglers, 89.5” x 97”

Courtesy of Echo Arts, Bozeman, MT.

Montana-based painter and writer Sandra Dal Poggetto speaks of key experiences in her youth, ones that have led her on a profound journey of rediscovery—enabled by her art practice and her passionate embrace of hunting. A lifelong Westerner, she grew up in the town of Sonoma in Northern California’s wine country. She describes that childhood:

Manzanita, chamisa, and oak surrounded my home. The mild Mediterranean climate of the coastal California hills invited outdoor play, and I accepted the invitation with pleasure. Often I saw blacktail deer tracks in the powdered soil, or jackrabbits, and heard the call of quail during quiet morning and evening hours. The smooth, taut skin of the manzanita I caressed. I pinched and ran my nails down the slender, flexible chamisa branch so that I could hold the stubby needles in my palm.

Within the concentrations of chamisa was a network of animal tunnels aglow with a diffused light. Through these I would crawl until I came to the wide trunk of a live oak whose coarse, gray limbs I would climb and, through the deep green of small, waxy leaves, look out over the valley. The slopes of chaparral, I knew, were shaped by fire, and the valley below was favored with river water.[1]

This full-bodied embrace of landscape ended for Dal Poggetto in adolescence. She writes, "The power of postwar commercial America—promoted by pervasive television, magazines, and radio—sucked me into a virtual world devoid of nature. Hello, Andy Warhol."[2]. For Dal Poggetto, though, this change came with sudden and painful clarity.

She recalls walking in Jack London State Park near her home one day. "I wandered off the path and knelt down in the dry grass. Gradually, I sensed that a sheet of glass was separating me from everything around me: the trees, the grass, the brush. I felt alienated, separated from something that I loved."[3]

Dal Poggetto began to look for a way back from that alienation, not consciously, perhaps, but with determination. She turned to the study of art, attending the University of California, Davis, where she encountered a faculty comprised of such prominent figures in the Assemblage, Funk, and Bay Area Figuration movements as Robert Arneson, William T. Wylie, Manuel Neri, and Wayne Thiebaud. Though Thiebaud would influence her through his passion and seriousness, her most important teachers were Neri, whose blending of classical traditions with the gestural approach of Abstract Expressionism resonated with the young artist, and the painter Cornelia Schulz, whose ideas and shaped canvases—where, writes critic Julia Couzens, "reasoned geometry pushes against seduction’s looping pull"[4]— left an imprint.

An art-historical journey to Italy deepened this newfound passion for painting and drawing. Being of Italian heritage and having grown up where many Italian immigrants had settled, Dal Poggetto felt a natural affinity for things Italian, and during her UC Davis summer abroad (and on later visits to Italy), she became entranced with Etruscan funerary art and the frescoes of early Renaissance masters, particularly Giotto.

She became a voracious student of art history. The artists whose works she found most congenial ranged from the anonymous Greek figure-vase painters to Delacroix and Goya, Degas and Matisse, Mark Rothko and Cy Twombly, Emily Carr and Joan Mitchell, Philip Guston and Susan Rothenberg, and her favorite out of the Bay Area tradition, Richard Diebenkorn. Paul Cezanne, perhaps more than any other painter, was for her always "at the center." She loved his ability to capture the "incredible tension that is life," but she was equally delighted that he spent so much time in the countryside, losing himself in his preferred places. She saw this practice not only as artistic discipline, but as a strategy for "extending his childhood," remaining ever in touch with the natural world—one of her own life goals.[5]

Now irretrievably committed to the life of an artist, she would begin to find early recognition for her own work. After graduating from UC Davis in 1975 and completing an MFA at San Francisco State University in 1982, she had her first solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Dana Reich Gallery in 1985. The reception for this early work was markedly enthusiastic. Widely published critic Jerome Tarshis wrote, "Of all the first shows I remember seeing . . . the one that most knocked me out was Sandra Dal Poggetto’s. . . . Her newer work is reminiscent of cave and Egyptian wall painting in its emphasis on outline and its earthy colors. . . . her work suggests she is on her way to the kind of mastery that could easily put her on the covers of art magazines."[6] Another critic lauded her "images of elliptical birds darting above a vast, achingly bare landscape" and the "disturbing and subtly drawn contrast between radiant landscape and . . . struggling, shapeless human forms."[7]

Dal Poggetto notes, "I now see that painting has been a conduit back to that unalienated relation with the natural world,"[8] but it took more than an art practice to recover the pure joy in nature she had experienced as a child. When she met her husband, writer and conservationist Brian Kahn, he introduced her to the discipline and pleasures of hunting. She quickly became a convert, for more complex reasons perhaps than the average novice. Hunting became a second, essential conduit out of alienation. She writes:

Through hunting, I experience the sensation of a place. My body becomes more permeable; my senses simultaneously relax and intensify. I become vividly conscious of the swell of a hillside, the shape of a meadow, the color and texture of wild rye, the snap of a twig under hoof, the chittering alarm of a squirrel, the chill and density of cold air. A breeze at my back, whoosh of thrush, flick of a tail. There are no words. I respond to these cues with caution, delicacy, discernment, patience, and then action.[9]

Then, in the late 1980s, her husband Brian took the job of executive director of the Montana Nature Conservancy, and they moved to Helena. For a contemporary artist hoping to find a congenial local art scene, this may not have been an ideal move. At that time, Montana had a few small museums dedicated to modern and contemporary art, but almost no private galleries—commercial or otherwise—that ventured beyond the traditions of Western art and straight landscape. On the other hand, and more importantly, Dal Poggetto had literally reversed the ratio of humans to landscape. From densely populated Northern California, she had come to a place of vast spaces sparsely populated by people but unimaginably alive with plants and animals. Though from an art-world perspective she did find it lonely, here she met and conversed with conservationists, archaeologists, and geologists whose rich knowledge of her new home only added to her determination to express in her art a deeper connectedness to the natural world. She became aware of the rich pictographic art created by Indigenous people throughout the region. She grew fascinated by the fossil remains embedded in the stones of the Rocky Mountain Front. She was drawn to remnants of almost lost ecosystems.

In her early paintings, Dal Poggetto posited a critique of technological man. Though she is wonderfully skilled at the art of drawing (see Indigenous, 1987), she soon turned to simplified forms to represent the human. Happening upon Henry Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, she began using these stylized symbols in place of more realistic depictions. In the section on "Accommodations and Travel," she found the touching "Lost Child" symbol, often posted in airports, which would appear in several early 1990s works (see Latitude, 1991). Here, too, we see her newfound fascination with fossils and, in the case of Latitude, the delicate fishes embedded in the Green River Formation. Her Understory (1993) utilizes a version of the beloved PBS "Everyman P-Head" (albeit with a bigger nose; "I like big noses," she notes [10]). This drawing suggests that underlying the barely animate P-Head still stands the swirling, vividly alive phenomenal world. Just as her humans were becoming more formulaic, her investigations of landscape grew richer and ever more nuanced.

Indigenous

1987, egg tempera, soft pastel, charcoal on canvas, 84” x 96”

Collection of Missoula Art Museum, gift of John W. & Carol L. H. Green.

Latitude

1991, ink on paper, 8.5” x 11”

Collection of the artist.

Understory

1993, ink on paper, 5.5” x 7”

Private collection.

Her Botanical Writings series of the mid-90s continued to erode the human presence in her work. Another new series, Meditations on Hunting (after the essay by Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset), marked her turn to full abstraction. She says, "Through abstraction, I really could include more, not less . . . of my full experience" in the landscape. And yet, she wasn’t entirely satisfied. In her view, these works remained "quite formal, composing visual elements of shape, color, texture, value" and were therefore "too general in feeling"—not wild enough.[11]

Then, at the start of the 21st century, "an important thing" happened. While visiting New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dal Poggetto wandered into the Pre-Columbian galleries, where she found herself confronted by stunning feather works created by the Wari culture of Peru. Remarkably modern in feeling (though they date from before the Spanish conquest), these cotton or leather panels—with rows of feathers attached in abstract designs of elegant simplicity—were "mesmerizing" to Dal Poggetto, and they felt "instantly familiar."[12]

"I understood," she says, "that these were feathers from birds that were hunted by people in a very particular place, in a very particular landscape."[13] She quickly realized that, by using the feathers of the game birds she harvested back home, she could create her own feather works—not as imitations of the ancient Wari masterpieces but instead paying homage to her own particular place and the birds who dwell there. At first she created these works with feathers only, using thread to attach the tail feathers of wild turkey, blue grouse, pheasant, and ruffed grouse to handmade paper in her own elegant patterns (see The Stillwater, 2005).

The Stillwater

2005, wild turkey feathers, thread on paper, 31” x 22”

Collection of Nancy Brown Negley.

Soon, Dal Poggetto wanted to expand the field, combining the feathers with marks of her own making (see Breed No. 7, 2012). Creating the feather works led her deeper into the world of Montana’s mountains and high plains and away from the formality still evident in the early Meditations on Hunting. Instead of imposing the modernist grid on these new hybrid works, she upended the usual order of things. She told critic Mark Stevens in 2002: "I didn’t like the idea of imposing the grid on the feather. So I reversed it. . . . The feather dictates the organization of the space. The feather is an uncompromising structure, so the painting is determined by its shape."[14] Stevens, co-author (with his wife, Annalyn Swan) of the Pulitzer-winning biography de Kooning: An American Master and the recent Francis Bacon: Revelations, adds: "The feathers themselves were already full of internal grids, lyrical geometric forms and repeating patterns. (Few things in this world have the beautiful rigor of a pheasant feather.) But they were not strict rectangles, so Dal Poggetto organized the shapes in her grids to reflect their various idiosyncratic forms."[15]

Breed No. 7

2012, soft pastel, Hungarian partridge feathers, brass wire on paper, 47” x 42”

Private collection.

Released from the more traditional formality of her earlier work, she launched several series of new works with more organic and improvisatory approaches. These include the In Situ, Breed, Relict, Fen, Targhee, American Fork, Surprise Creek, and Archive series, each distinct from the next, ranging widely in scale, materials, and conception (see Breed No. 14, Fen No. 1, and Surprise Creek No. 1). Taking the lead from the formal qualities of feathers, lines traced on the landscape by animal trails, and the synesthetic impressions evoked by particular experiences within specific landscapes, Dal Poggetto created works distinctly her own. Always working "according to impulse," she sought to "participate in all the energies" of a landscape. She began to call the marks she made in these works "condensations" of the experiences that resonate through her full sensorium—sounds, smells, textural impressions, the tiniest of visual details, an uncanny sense of the vastness of geologic time—while immersed in a High Plains landscape. "Somehow, it’s all in there," she says. "Big space and things close at hand."[16]

Breed No. 14

2017, soft pastel, Canada goose feathers on paper, 13.75” x 19”

Private collection.

Fen No. 1

2018, oil, mallard pelts on gessoed cardboard, 9” x 12”

Private collection.

Surprise Creek No. 1

2017-18, oil, whitetail deer hide on cardboard, 10” x 16”

Private collection.

When Sandra Dal Poggetto calls these abstract marks she makes on canvas and paper "condensations," one is reminded of the poet Lorine Niedecker, another artist who spoke deeply out of a particular place. The watery environment around Blackhawk Island, Wisconsin, was Niedecker’s lifelong home, and yet she maintained unbreakable ties with cutting-edge artists in the larger world—Louis Zukofsky in Brooklyn Heights, Cid Corman in Japan, and Basil Bunting in Northumbria. Of the discipline of making poems, Niedecker wrote, "No layoff/ from this/condensery." This urge to condense arises in both artists not because of some art-world imperative, but because both seek to embody a deeper reality. Just as Dal Poggetto insists on geologic time as an inescapable dimension of landscape, Niedecker reminds us, "In every part of every living thing/ is stuff that once was rock."[17] Critic and poet Douglas Crase has called this strain in American arts the "evolutional sublime." In an essay on Niedecker, he expands on the notion:

When I think of the [Walt] Whitman who found he incorporates gneiss, the [Gertrude] Stein who says anybody is as their land and air is, the [Wallace] Stevens who locates mythology in stone out of our fields or from under our mountains, then I have to admit that the sublimest American poetry has always read to me as if it would rather restore . . . a wealth that is wild outside the human voice.[18]

While Dal Poggetto’s marks concentrate the richness of experience, her recent works are her most expansive to date. In particular, her American Fork paintings—both in physical scale and through the import of their content—stand as the apotheosis of her ongoing exploration. In paintings as large as nine feet square (see American Fork No. 15, 2016-2017), Dal Poggetto stretches far beyond the limitations of the "picture window" of classical landscape painting. Perhaps that traditional format reminds her too much of the sheet of glass that descended to separate her, seemingly irrevocably, from her beloved Sonoma landscape. Her first American Fork works still used a traditional horizontal/vertical grid, but soon she found another organizing principle.

In a 2014 conversation with Mark Stevens (her greatest interpreter) at the University of Montana, she speaks of rotation as this principle, taking into account the 360-degree horizon line and the movement of the heavens. "That is a very different awareness of landscape," she adds, "and I find it very exciting." She calls this "radial" composition. Again, seeking to construct her works in keeping with the spirit of the landscape, she notes, "You find radial composition all over the landscape. You find it in plant structures, in marine life—I am surrounded by fossils up on the East Front. That brings in another dimension, of time and of scope." Mark Stevens affirmed, "It is quite mysterious how you get that sense of scale and 360 in what is actually a two-dimensional work." He went on to say that the experience of viewing these paintings involves a "surrounding kind of feeling." These expanded landscapes, crafted out of oil, soft pastel, charcoal, and buckskin danglers, are populated by Dal Poggetto’s "condensed little nodes," her "quick little sharp notes" that suggest but do not describe.[19]

American Fork No. 15

2016-17, oil, soft pastel, charcoal, buckskin danglers on canvas, 111” x 108”

Courtesy of Echo Arts, Bozeman, MT.

If there is any artist whose work most resonates with Dal Poggetto with regard to the American Fork series, it is the American Cy Twombly, who spent the bulk of his adult life in Italy. This may seem an unlikely pairing. Twombly’s paintings, in Dal Poggetto’s words, represent a new form of history painting. She says, "Yes, Twombly is an influence: his evocation of deep physical space—the Mediterranean land and sea—and historical/mythological time with the combination of graphic media and oil paint marks, both abstract and representational on the ground of the canvas. The dynamic of pencil and oil marks in an unspecified space is quite thrilling somehow. An activated space."[20]

Dal Poggetto’s most recent painting, Archive No. 1, achieves a new direction in her work and reveals, as do the later American Fork paintings, a clear and felicitous connection to Twombly’s use of space. After two decades, Archive No. 1 brings the image back into Dal Poggetto’s work, but within the radial composition she invented for the American Fork paintings. Here are all the images that were important in her 1990s work: the PBS P-Head (standing in for technological man, now more technological than ever), all manner of plant life, and fish and amphibians of various sorts. No longer anchored to a stable ground, this swirling, more-than-360-degree landscape makes it impossible to tell up from down, the living creature from the fossilized one. This painting might be seen as a chilling warning: Does the Archive title suggest that these relicts are all that remain of a once-vibrant world? Or is this work a celebration of what Dal Poggetto calls the "at-onceness" of all things? Clearly, we can stand before this vast painting and let its ambiguities wash over us, challenging us to contemplate a question its creator once asked during an interview: "Are we, as a species, destined to become fossils ourselves?"[21]

Archive No. 1

2020, charcoal, oil on canvas, 86” x 88”

Courtesy of Echo Arts, Bozeman, MT.

In his influential essay, "The Symbol of the Archaic," the great Kentucky polymath Guy Davenport argues that in early European modernism many artists—Picasso, Brancusi, Ezra Pound, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), and James Joyce foremost among them—participated in a "renaissance of the archaic." Through their embrace of the art of other cultures and eras, from Cycladic sculpture to the cave paintings of Lascaux, ancient Chinese lyrics to the fragments of Heraclitus, Greek myth to the "color and robustness of the Etruscans," these artists sought to restore, in Davenport’s words, the freshness of springtime cultures. He asserts, "[T]he impulse to recover beginnings and primal energies grew out of a feeling that man in his alienation was drifting tragically away from what he had first made as poetry and design and as an understanding of the world." After the horrors of trench warfare and mechanized death in World War I, many moderns sought new vitality and meaning wherever they could find them.[22]

Like those early modernists, and in the face of fresh disasters (man-made climate change, accelerating species extinction, the wholesale annihilation of ecosystems), Sandra Dal Poggetto is intent on recovering primal energies. Through the rigor of her art, she seeks to offer new ways of perceiving, and being with, this actual physical world we share. Her project has little to do with cultural artifacts. Instead, it aims to recover that wonderfully intimate connection with the natural world she experienced as a child. Though, at first glance, some may find her abstract art difficult to understand, in fact these tender, expansive, unsettlingly gorgeous works create a poetic space—both spiritual and political—that can help us to live more fully. As Douglas Crase says, they "restore . . . a wealth that is wild outside the human voice."

Notes

1. Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Duccio in the Eye of the Hunt: Modern Connections between the Chase and Art," Gray’s Sporting Journal (1996), 21:6. back to essay ↩

2. Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Primal Colors," Center for Humans and Nature website, Chicago. Retrieved from: https://www.humansandnature.org/hunting-sandra-dal-poggetto back to essay ↩

3. Sandra Dal Poggetto, interview by Brandon Reintjes, Sandra Dal Poggetto: Meditations on the Field (Missoula: Montana Museum of Art & Culture, 2014), 11. Retrieved from: https://www.blurb.com/books/5518565-sandra-dal-poggetto-meditations-on-the-field back to essay ↩

4. Julia Couzens, "Cornelia Schulz and Carrie Lederer @ Patricia Sweetow," Squarecylinder, November 29, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.squarecylinder.com/2017/11/cornelia-schulz-and-carrie-lederer-patricia-sweetow/ back to essay ↩

5. Sandra Dal Poggetto, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, September 4, 2019. back to essay ↩

6. Jerome Tarshis, "Jerome’s Unknowns," San Francisco FOCUS (July 1985), 27. back to essay ↩

7. Kate Regan, "Shimmering Rays and a Troubled Lyricism," San Francisco Chronicle (February 2, 1985), 75. back to essay ↩

8. Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Hidden in the Wide Open," a talk at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West (BBCW), Cody, WY, on the occasion of the acquisition of her work, American Fork No. 4, by the Whitney Western Art Museum , November 11, 2014. Retrieved from: https://centerofthewest.org/2014/11/04/sandra-dal-poggetto-hidden-wide-open/ back to essay ↩

9. Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Wildtime," Basalt (2015), 10:1. Retrieved from: https://www.eou.edu/basalt/basalt-volume-10-number-1/featured-artist-sandra-dal-poggetto/ back to essay ↩

10. Sandra Dal Poggetto, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, November 3,2021. back to essay ↩

11. Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Hidden in the Wide Open," BBCW, 2014. back to essay ↩

12. Ibid. back to essay ↩

13. Ibid. back to essay ↩

14. Sandra Dal Poggetto, quoted in Mark Stevens, "Tensions, Paradoxes and Impurities: The Truth of the Matter," In Situ: New Paintings by Sandra Dal Poggetto (Billings: Yellowstone Art Museum, 2002), 6. back to essay ↩

15. Mark Stevens, "Tensions, Paradoxes and Impurities," In Situ, 6. back to essay ↩

16. Sandra Dal Poggetto, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, September 4, 2019; Sandra Dal Poggetto, "Hidden in the Wide Open," BBCW, 2014. back to essay ↩

17. Lorine Niedecker, "Lake Superior," Lorine Niedecker: Collected Works, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 232. back to essay ↩

18. Douglas Crase, "Niedecker and the Evolutional Sublime," Lake Superior (Seattle/New York: Wave Books, 2013), 28. back to essay ↩

19. Sandra Dal Poggetto and Mark Stevens, "Primal Colors: A Conversation," Montana Museum of Art & Culture, University of Montana, 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JkkWk-ogQcs back to essay ↩

20. Sandra Dal Poggetto, note to the author, February 7, 2020. back to essay ↩

21. Sandra Dal Poggetto, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, November 3, 2021. back to essay ↩

22. Guy Davenport, "The Symbol of the Archaic," The Geography of the Imagination (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1981), 20, 28. back to essay ↩

All Work by Sandra Dal Poggetto Included in HDJ Issue 33:

(Select an image to enlarge it and view credits)

Poet, editor, and cultural journalist Rick Newby is principal author of the monograph Theodore Waddell—My Montana: Paintings & Sculpture, 1959-2016, recipient of the High Plains Book Award, Art/Photography, 2018. He has also contributed major essays to the exhibition catalogs Matter + Spirit: Stephen De Staebler (de Young Museum, San Francisco, 2012), The Most Difficult Journey: The Poindexter Collections of American Modernist Painting (Yellowstone Art Museum, 2002), and A Ceramic Continuum: Fifty Years of the Archie Bray Influence (Holter Museum of Art, 2001). He is the editor of Writing Montana: Literature Under the Big Sky (with Suzanne Hunger), An Ornery Bunch: Tales and Anecdotes Collected by the W.P.A. Montana Writers’ Project (with Megan Hiller, Alexandra Swaney, and Elaine Peterson), The New Montana Story: An Anthology, and Roger Dunsmore’s On the Chinese Wall: New & Selected Poems, 1966-2018. Rick’s collection, A Regionalism That Travels: Essays & Talks on (Mostly) Montana Arts, is forthcoming from Drumlummon Institute in 2022. He makes his home in Helena, Montana.