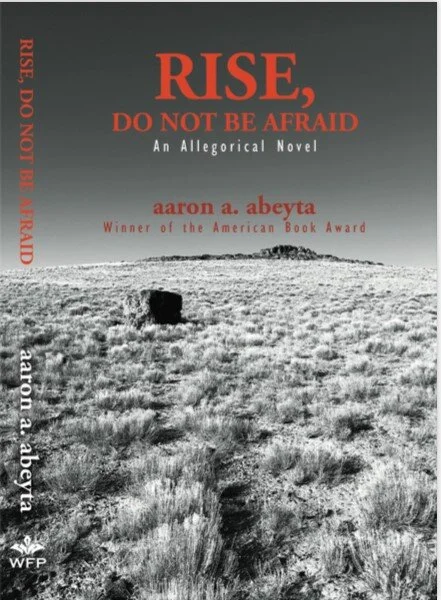

Aaron A. Abeyta’s

Rise, Do Not Be Afraid

Reviewed by Laura Pritchett

Wordfire Press, April 2021

Hardcover: $24.99

Aaron Abeyta’s first novel, Rise, Do Not Be Afraid, has an unusual central character—the town of Santa Rita. She is as changing—and as changeable—as any fictional human character, and just as vulnerable, as kind, as difficult, as unpredictable. She's also as complicated as her inhabitants—the herders, guitar players, lovers, mothers, healers, and the wounded. She is also real. The town of Santa Rita rests in a small valley in the Colorado-New Mexico area at the end of a dirt road, and although mostly abandoned now, it was a thriving community in the mid 1950s, which is when this novel is set.

Abeyta been writing about this landscape for 30 years, most notably in his poetry collections colcha, Rise, and As Orion Falls, and an epistolary book Letters from the Headwaters. This novel, originally published in 2007 by Ghost Road Press, was one of the tragic casualties of small-press demise. It went out of print and was largely undiscovered, although it was a finalist for the Premio Aztán Literary Prize and the Colorado Book Award. There is a certain great pleasure in seeing such a book re-released, particularly when it offers such a unique tale of a unique area.

Like his other books, this one is set in land Abeyta knows better than most in America could hope to know a place, outside of First Peoples, of course. Abeyta’s family first came to the area in 1844 and he is (rather incredibly), the seventh of nine generations. His family called this land home before it was broken into the United States, into states, into counties, into towns, a fact which contributes greatly to the understanding of the storytelling in the book. And it is a complicated place—in the bosque, in this landscape, the people are, as Abeyta writes, “made of Spain and oceans, Mexico and pyramids, mountains with cold blue lakes, of adobe and memory, of words, of acequias and rivers and rain, of bone and prayer, and of memory.”

Like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesberg, Ohio, or Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kittridge, we find that episodic narratives blend together to tell a complete story of a community. As the central character, the town holds all the stories that extend far beyond her walls—global concerns of war, hunger, family sagas, and perhaps, above all else, the gift and problems of language, the difficulty in finding honest and complete communication.

Related and unsurprisingly, the novel’s greatest gift is its poetry, and the novel is best approached with this in mind. Any line will slow—pleasantly—the reader with the rhythm and meter and metaphor. As one example, this: “abuelita scoops out with a tin cup, always the same cup, always the same tin cup balanced in her hand, not really measured but weighed by the soft thin fingers of her hands holding the tin cup, balanced really between the farmer’s grain, the earth’s rain, the acequias.” It’s the sort of line that becomes rhythmically ingrained in the mind, revealing a craftsmanship seen in his original genre.

In this vein, the novel purposefully pays homage to previous poets, which is another characteristic of Abeyta’s writing (Letters from the Headwaters was inspired by Richard Hugo, for example). Here you’ll find bits of Blake, Whitman, T.S. Eliot, and Merton, to name a few, though it is Rilke who is front-and-center. Indeed, reading this novel reminds one of this passage in Rilke’s essay, “For the Sake of a Single Poem”:

For poems are not, as people think, simply emotions (one has emotions early enough)—they are experiences. For the sake of a single poem, you must see many cities, many people and Things, you must understand animals, must feel how birds fly, and knows the gesture which small flowers make when they open in the morning.”*

Indeed, the experience of this book is to see many things, on many levels, all at once. While we hear the drumbeat of poetry, we also hear music (guitar, piano, flute, violin, whistling all make appearances), and we hear both Spanish and English, and we hear a clear nod to the oral tradition of storytelling. Abeyta jumps in time and space and point of view—and, importantly, most stories are told from at least three different perspectives, which is his way of indicating that stories are alive, changeable, dependent on perspective.

Ultimately, this becomes a novel that bears witness to the death of the main character—a pueblo and a way of life. Abeyta writes, “Santa Rita would disappear slowly and only a few would understand its loss. Santa Rita would die, but there are pieces of her with its people . . . Only a few would understand how the loss eventually equals the healing.” The gift of Abeyta’s book is to open that door to understanding the ghost of a place, its history, its people. Unlike the town, this book has been resurrected, which allows Santa Rita to live once again.

*Source: Rainer Maria Rilke, “For the Sake of a Single Poem,” The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke (New York: Vintage Books, 1989).

Aaron A. Abeyta is a Colorado native, Professor of English and the Mayor of Antonito, Colorado, his hometown. He is the author of four collections of poetry and one novel. For his book, colcha, Abeyta received an American Book Award and the Colorado Book Award. In addition, his novel, Rise, Do Not be Afraid, was a finalist for the 2007 Colorado Book Award and El Premio Aztlan. Abeyta was awarded a Colorado Council on the Arts Fellowship for poetry, and he is the former Poet Laureate of Colorado’s Western Slope, as named by the Karen Chamberlain Poetry Festival. Abeyta is also a recipient of a Governor’s Creative Leadership Award for 2017. Abeyta was a finalist for Colorado Poet Laureate, 2019.